- Home

- Abulhawa, Susan

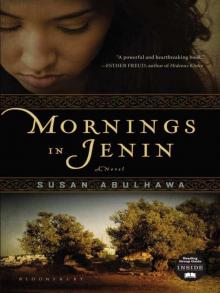

Mornings in Jenin

Mornings in Jenin Read online

MORNINGS IN JENIN

A NOVEL

SUSAN ABULHAWA

For Natalie,

and for Seif

CONTENTS

Prelude

I. El Nakba

(the catastrophe)

1 The Harvest

2 Ari Perlstein

3 The No-Good Bedouin Girl

4 As They Left

5 “Ibni! Ibni!”

6 Yehya’s Return

7 Amal Is Born

II. El Naksa

(the disaster)

8 As Big as the Ocean andAll Its Fishes

9 June in the Kitchen Hole

10 Forty Days Later

III. The Scar of David

11 A Secret, Like a Butterfly

12 Yousef, the Son

13 Moshe’s Beautiful Demon

14 Yousef, the Man

15 Yousef, the Prisoner

16 The Brothers Meet Again

17 Yousef, the Fighter

18 Beyond the First Row of Trees

19 Yousef Leaves

20 Heroes

21 Tapered Endings

22 Leaving Jenin

23 The Orphanage

IV. El Ghurba

(state of being a stranger)

24 America

25 The Telephone Call from Yousef

V. Albi fi Beirut

(my heart in Beirut)

26 Majid

27 The Letter

28 “Yes”

29 Love

30 A Story of Forever

31 Philadelphia, Again

32 A Story of Forever, Forever Untold

33 Pity the Nation

34 Helpless

35 The Month of Flowers

36 Yousef, the Avenger

VI. Elly Bayna

(what there is between us)

37 A Woman of Walls

38 Here, There, and Yon

39 The Telephone Call from David

40 David and Me

41 David’s Gift

42 My Brother, David

VII. Baladi

(my country)

43 Dr. Ari Perlstein

44 Hold Me, Jenin

VIII. Nihaya o Bidaya

(an end and a beginning)

45 For the Love of Daughters

46 Pieces of God

47 Yousef, the Cost of Palestine

Author’s Note

Glossary

References

PRELUDE

Jenin

2002

AMAL WANTED A CLOSER look into the soldier’s eyes, but the muzzle of his automatic rifle, pressed against her forehead, would not allow it. Still, she was close enough to see that he wore contacts. She imagined the soldier leaning into a mirror to insert the lenses in his eyes before getting dressed to kill. Strange, she thought, the things you think about in the district between life and death.

She wondered if officials might express regret for the “accidental” killing of her, an American citizen. Or if her life would merely culminate in the dander of “collateral damage.”

A lone bead of sweat traveled from the soldier’s brow down the side of his face. He blinked hard. Her stare made him uneasy. He had killed before, but never while looking his victim in the eyes. Amal saw that, and she felt his troubled soul amid the carnage around them.

Strange, again, I am unafraid of death. Perhaps because she knew, from the soldier’s blink, that she would live.

She closed her eyes, reborn, the cold steel still pushing against her forehead. The petitions of memory pulled her back, and still back, to a home she had never known.

I.

EL NAKBA

(the catastrophe)

ONE

The Harvest

1941

IN A DISTANT TIME, before history marched over the hills and shattered present and future, before wind grabbed the land at one corner and shook it of its name and character, before Amal was born, a small village east of Haifa lived quietly on figs and olives, open frontiers and sunshine.

It was still dark, only the babies sleeping, when the villagers of Ein Hod prepared to perform the morning salat, the first of five daily prayers. The moon hung low, like a buckle fastening earth and sky, just a sliver of promise shy of being full. Waking limbs stretched, water splashed away sleep, hopeful eyes widened. Wudu, the ritual cleansing before salat, sent murmurs of the shehadeh into the morning fog, as hundreds of whispers proclaimed the oneness of Allah and service to his prophet Mohammad. Today they prayed outdoors and with particular reverence because it was the start of the olive harvest. Best to climb the rocky hills with a clean conscience on such an important occasion.

Thus and so, by the predawn orchestra of small lives, crickets and stirring birds—and soon, roosters—the villagers cast moon shadows from their prayer rugs. Most simply asked for forgiveness of their sins, some prayed an extra rukaa. In one way or another, each said, “My Lord Allah, let Your will be done on this day. My submission and gratitude is Yours,” before setting off westward toward the groves, stepping high to avoid the snags of cactus.

Every November, the harvest week brought renewed vigor to Ein Hod, and Yehya, Abu Hasan, could feel it in his bones. He left the house early with his boys, coaxing them with his annual hope of getting a head start on the neighbors. But the neighbors had similar ideas and the harvest always began around five a.m.

Yehya turned sheepishly to his wife, Basima, who balanced the basket of tarps and blankets on her head, and whispered, “Um Hasan, next year, let’s get up before them. I just want to get an hour start over Salem, that toothless old bugger. Just one hour.”

Basima rolled her eyes. Her husband revived that brilliant idea every year.

As the dark sky gave way to light, the sounds of reaping that noble fruit rose from the sun-bleached hills of Palestine. The thumps of farmers’ sticks striking branches, the shuddering of the leaves, the plop of fruit falling onto the old tarps and blankets that had been laid beneath the trees. As they toiled, women sang the ballads of centuries past and small children played and were chided by their mothers when they got in the way.

Yehya paused to massage a crick in his neck. It’s nearly noon, he thought, noting the sun’s approach to zenith. Sweat-drenched, Yehya stood on his land, a sturdy man with a black and white kaffiyeh swathing his head, the hem of his robe tucked in his waist sash in the way of the fellaheen. He surveyed the splendor around him. Mossy green grass cascaded down those hills, over the rocks, around and up the trees. The sanasil barriers, some of which he had helped his grandfather repair, spiraled up the hills. Yehya turned to watch Hasan and Darweesh, their chest muscles heaving beneath their robes with every swing of their sticks to knock the olives loose. My boys! Pride swelled Yehya’s heart. Hasan is growing strong despite his difficult lungs. Thanks be to Allah.

The sons worked on opposite sides of each tree as their mother trailed them, hauling away blankets of fresh olives to be pressed later that day. Yehya could see Salem harvesting his yield in the adjacent grove. Toothless old bugger. Yehya smiled, though Salem was younger than he. In truth, his neighbor had always a quality of wisdom and a grandfatherly patience that gave of itself from a face mapped by many years of carving olive wood outdoors. He had become Haj Salem after his pilgrimage to Mecca, and the new title bestowed him with age beyond that of Yehya. By evening, the two friends would be smoking hookahs together, arguing over who had worked hardest and whose sons were strongest. “You’re going to hell for lying like that, old man,” Yehya would say, bringing the pipe to his lips.

“Old man? You’re older than me, you geezer,” Salem would say.

“At least I still have all my teeth.”

“Okay. Get out the board so

I can prove once again who’s better.”

“You’re on, you lyin’, toothless, feeble son of your father.”

Games of backgammon over bubbling hookahs would settle this annual argument and they would stubbornly play until their wives had sent for them several times.

Satisfied by the morning’s pace, Yehya performed the thohr salat and sat on the blanket where Basima had arranged the lentils and makloobeh with lamb and yogurt sauce. Nearby, she set another meal for the migrant helpers, who gratefully accepted the offering.

“Lunch!” she called to Hasan and Darweesh, who had just completed their second salat of the day.

Seated around the steaming tray of rice and smaller plates of sauces and pickles, the family waited for Yehya to break the bread in the name of Allah. “Bismillah arrahman arraheem,” he began, and the boys followed, hungrily reaching for the rice to ball it into bites with yogurt.

“Yumma, nobody is as good a cook as you!” Darweesh the flatterer knew how to assure Basima’s favor.

“Allah bless you, son.” She grinned and moved a tender piece of meat to his side of the rice tray.

“What about me?” Hasan protested.

Darweesh leaned to his older brother’s ear, teasing, “You aren’t as good with the ladies.”

“Here you are, darling.” Basima tore off another piece of good meat for Hasan.

The meal was over quickly without the usual lingering over halaw and coffee. There was more work to be done. Basima had been filling her large baskets, which the helpers would carry to the olive press. Each of her boys had to press his share of olives the day of their harvest or else the oil might have a rancid taste.

But before heading back, a prayer was offered.

“First, let us give thanks for Allah’s bounty.” Yehya issued his command, pulling an old Quran from the pocket of his dishdashe. The holy Book had belonged to his grandfather, who had nurtured these groves before him. Although Yehya could not read, he liked to look at the pretty calligraphy while he recited surahs from memory. The boys bowed, impatiently listening to their father sing Quranic verses, then raced down the hill when granted their father’s permission to head for the press.

Basima hoisted a basket of olives onto her head, lifted in each hand a woven bag full of dishes and leftover food, and proceeded down the hill with other women who balanced urns and belongings on their heads in plumb uprightness. “Allah be with you, Um Hasan,” Yehya called to his wife.

“And you, Abu Hasan,” she called back. “Don’t be long.”

Alone now, Yehya leaned into the breeze, blew gently into the mouthpiece of his nye, and felt the music emerge from the tiny holes beneath his fingertips. His grandfather had taught him to play that ancient flute and its melodies gave Yehya a sense of his ancestors, the countless harvests, the land, the sun, time, love, and all that was good. As always, at the first note, Yehya raised his brows over closed eyelids, as if perpetually surprised by what majesty his simple hand-carved nye could make from his breath.

Several weeks after the harvest, Yehya’s old truck was loaded. There was some oil, but mostly almonds, figs, a variety of citrus, and vegetables. Hasan put the grapes on top so they would not be crushed.

“You know I’d rather you not go all the way to Jerusalem,” Yehya said to Hasan. “Tulkarem is only a few kilometers away and gasoline is expensive. Even Haifa is closer, and their markets are just as good. And you never know what son-of-a-dog Zionist is hiding in the bushes or what British bastard is going to stop you. Why make the trip?” But the father already knew why. “You taking this long ride to meet up with Ari?”

“Yaba, I gave him my word that I was coming,” Hasan answered his father, somewhat pleadingly.

“Well, you’re a man now. Watch yourself on the road. Be sure to give your aunt whatever she needs from your cart and tell her we want her to visit soon,” Yehya said, then called to the driver, who was well known to everyone and whose features asserted their common lineage. “Drive in the protection of Allah, son.”

“Allah give you long life, Ammo Yehya.”

Hasan kissed his father’s hand, then his forehead, reverent gestures that filled Yehya with love and pride.

“Allah smile on you and protect you for all your days, son,” he said as Hasan clambered into the back of the truck.

As they drove away, Darweesh cantered alongside on Ganoosh, his beloved Arabian steed. “Let’s race. I’ll give you an hour head start since the truck is weighed down,” he challenged Hasan.

“Go race the wind, Darweesh. That’s more up to your speed than this old clunker. Go on, I’ll meet you in Jerusalem at Amto Salma’s house.”

Hasan watched his younger brother fly away bareback, the hatta tight around his head, its loose ends grabbing at the wind behind him. Darweesh was the best rider for miles around, maybe the best in the country, and Ganoosh was the fastest horse Hasan had ever seen.

Along the dusty road, the land rose in sylvan silence, charmed with the scents of citrus blooms and wild camphires. Hasan opened the pouch that his mother filled each day, pinched off a glob of her sticky concoction, and raised it to his nose. He breathed it in as deeply as his asthmatic lungs would allow. Oxygen diffused through his veins as he opened one of the secret books Mrs. Perlstein, Ari’s mother, had instructed him to study.

TWO

Ari Perlstein

1941

ARI WAS WAITING BY the Damascus Gate, where the boys had first met four years earlier. He was the son of a German professor who had fled Nazism early and settled in Jerusalem, where his family rented a small home from a prominent Palestinian.

The two boys had become friends in 1937 behind the pushcarts of fresh fruits, vegetables, and dented cans of oil in Babel Amond market, where Hasan had sat reading a book of Arabic poems. The small Jewish boy with large eyes and an unsure smile had started toward Hasan. He moved with a limp, the legacy of a badly healed leg and the Brown Shirt who had broken it. He had bought a large red tomato, pulled out a pocketknife, and cut it, keeping half and offering the rest to Hasan.

“Ana ismi Ari. Ari Perlstein,” the boy had said.

Intrigued, Hasan had taken the tomato.

“Goo day sa! Shalom!” Hasan had tried the only non-Arabic words he knew and motioned for the boy to sit.

Though Ari could improvise some Arabic, neither spoke the other’s language. But they quickly found commonality in their mutual sense of inadequacy.

“Ana ismi Hasan. Hasan Yehya Abulheja.”

“Salam alaykom,” Ari had replied. “What book are you reading?” he had asked in German, pointing.

“Book.” English. “Dis, book.”

“Yes.” English. “Kitab.” Book, Arabic. “Yes.” They had laughed and eaten more tomato.

Thus a friendship had been born in the shadow of Nazism in Europe and in the growing divide between Arab and Jew at home, and it had been consolidated in the innocence of their twelve years, the poetic solitude of books, and their disinterest in politics.

Decades after war had divided the two friends, Hasan told his youngest child, a little girl named Amal, about his boyhood friend. “He was like a brother,” Hasan said, closing a book that had been given to him by Ari in the autumn of their boyhood.

Though Hasan would experience a colossal physical growth, at twelve he was a sickly boy whose lungs hissed with every breath. The labor of his breathing pushed him to the sidelines of the strict confederacies of boys and their rough play. Likewise, Ari’s limp invited the relentless mockery of his classmates. Both possessed an air of recoil that recognized itself in the other, and each, at a young age and in his own world and language, had found refuge in the pages of poets, essayists, and philosophers.

What had been a bothersome occasional travel to Jerusalem became a welcome weekly trip, for Hasan would find Ari waiting there and they would pass the hours teaching each other the words in Arabic, German, and English for “apple,” “orange,” “olive.” “The onions are one

piaster the pound, ma’am,” they practiced. From behind the cart’s rows of fruit and vegetables, they privately poked fun at the Arab city boys, with their affected speech and fancy clothes that were little more than displays of servile admiration for the British.

Ari even began to wear traditional Arab garb on weekends and often returned to Ein Hod with Hasan. Immersed in the melodies of Arabic speech and song and the flavors of Arabic food and drink, Ari gained a respectable command of his friend’s language and culture, which in no small measure would contribute to his tenured professorship at Hebrew University decades later. Similarly, Hasan learned to speak German, to read haltingly some of the English volumes in Dr. Perlstein’s library, and to appreciate the traditions of Judaism.

Mrs. Perlstein loved Hasan and was grateful for his friendship with her son, and Basima received Ari with similar motherly enthusiasm. Although they never met face-to-face, the two women came to know one another through their sons and each would send the other’s boy home loaded with food and special treats, a ritual that Hasan and Ari grudgingly endured.

At thirteen, a year before Hasan’s formal schooling was to end, he asked his father’s permission to study with Ari in Jerusalem. Fearful that further education would take his son away from the land he was destined to inherit and farm, Yehya forbade it.

“Books will do nothing but come between you and the land. There will be no school with Ari and that is all I will say on the matter.” Yehya was certain he made the right decision. But years later, Yehya would reproach himself with deep consternation and regret for denying what Hasan had dearly wanted. For this decision, one day Yehya would beg his son’s forgiveness as they all camped at the mercy of the weather, not far from the home to which they could never return. Yehya, a withering refugee in the unfamiliar dilapidation of exile, would weep on Hasan’s forgiving shoulders. “Forgive me, son. I cannot forgive myself,” Yehya would cry. And it was for the same decision and subsequent regret and heartbreak that Hasan would resolve, with determined hard labor and its pittance pay, that his children would receive an education. For this decision, Hasan would tell his little girl, Amal, many years later, “Habibti, we have nothing but education now. Promise me you’ll take it with all the force you have.” And his little girl would promise the father she adored.

Mornings in Jenin

Mornings in Jenin